Fearing the spread of coronavirus, jails and prisons remain on lockdown. Visitors are unable to see their loved ones serving time, forcing friends and families to use prohibitively expensive video visitation services that often don’t work.

But now the security and privacy of these systems are under scrutiny after one St Louis-based prison video visitation provider had a security lapse that exposed thousands of phone calls between inmates and their families, but also calls with their attorneys that were supposed to be protected by attorney-client privilege.

HomeWAV, which serves a dozen prisons across the U.S., left a dashboard for one of its databases exposed to the internet without a password, allowing anyone to read, browse and search the call logs and transcriptions of calls between inmates and their friends and family members. The transcriptions also showed the phone number of the caller, which inmate, and the duration of the call.

Security researcher Bob Diachenko found the dashboard, which had been public since at least April, he said. TechCrunch reported the issue to HomeWAV, which shut down the system hours later.

In an email, HomeWAV chief executive John Best confirmed the security lapse.

“One of our third-party vendors has confirmed that they accidentally took down the password, which allowed access to the server,” he told TechCrunch, without naming the third-party. Best said the company will inform inmates, families and attorneys of the incident.

Somil Trivedi, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU’s Criminal Law Reform Project, told TechCrunch: “What we see again and again is that the rights of incarcerated people are the first to be trampled when the system fails — as it always, invariably does.”

“Our justice system is only as good as the protections for the most vulnerable. As always, people of color, those who can’t afford lawyers, and those with disabilities will pay the highest price for this mistake. Technology cannot fix the fundamental failings of the criminal legal system — and it will exacerbate them if we’re not deliberate and cautious,” said Trivedi.

Inmates have almost no expectations of privacy, and nearly all prisons in the U.S. record the phone and video calls of their inmates — even if it’s not disclosed at the beginning of each call. Prosecutors and investigators are known to listen back to recordings in case an inmate incriminates themselves on a call.

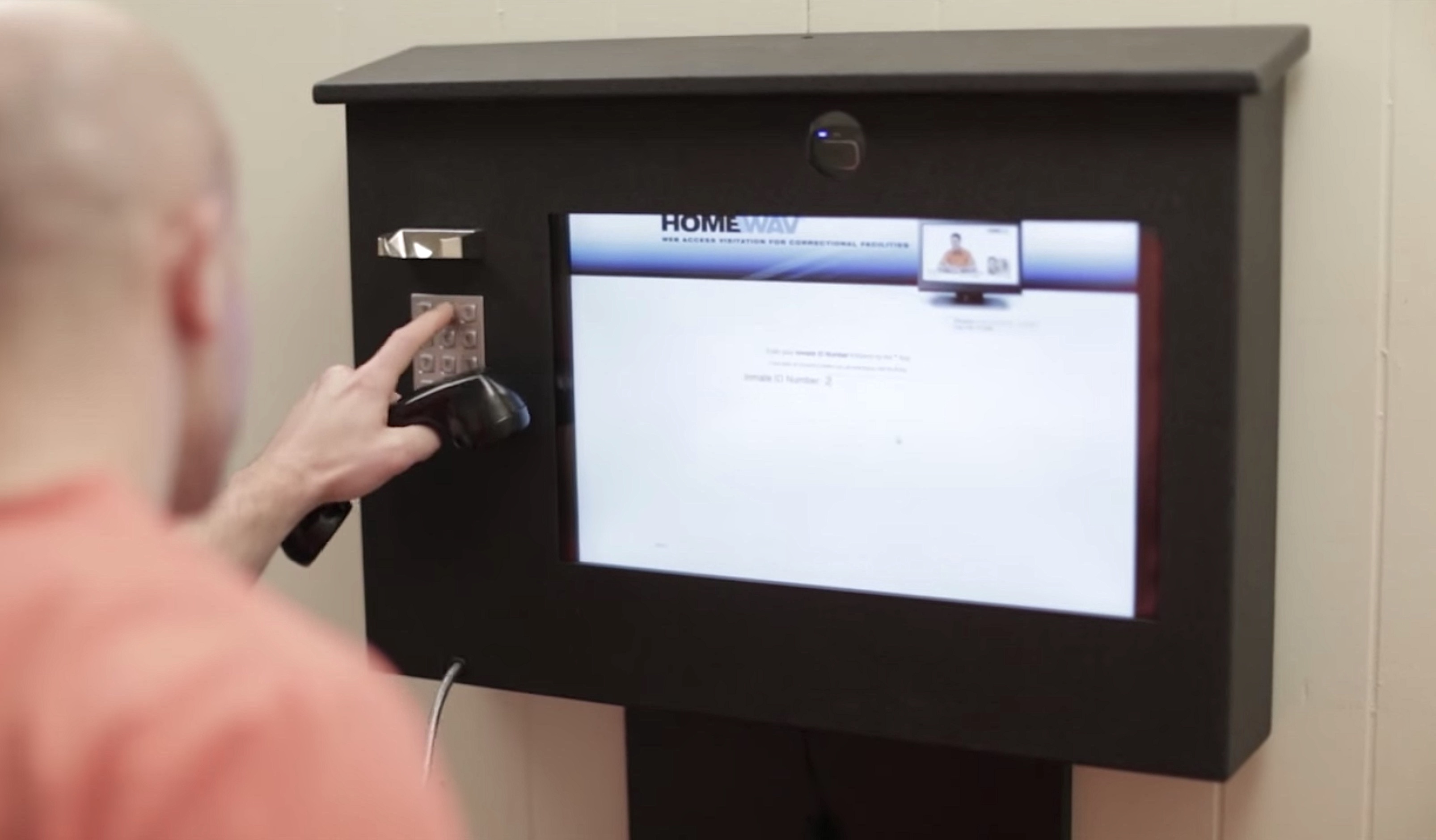

HomeWAV, a prison video visitation tech company, exposed thousands of phone calls between inmates and their families, but also calls with their attorneys that were supposed to be protected by attorney-client privilege. (Image: HomeWAV/YouTube)

The calls between inmates and their attorneys, however, are not supposed to be monitored because of attorney-client privilege, a rule that protects the communications between an attorney and their client from being used in court.

Despite this, there are known cases of U.S. prosecutors using recorded calls between an attorney and their incarcerated clients. Last year, prosecutors in Louisville, Ky., allegedly listened to dozens of calls between a murder suspect and his attorneys. And, earlier this year defense attorneys in Maine said they were routinely recorded by several county jails, and their calls protected under attorney-client privilege were turned over to prosecutors in at least four cases.

HomeWAV’s website says: “Unless a visitor has been previously registered as a clergy member, or a legal representative with whom the inmate is entitled to privileged communication, the visitor is advised that visits may be recorded, and can be monitored.”

But when asked, HomeWAV’s Best would not say why the company had recorded and transcribed conversations protected by attorney-client privilege.

Several of the transcriptions reviewed by TechCrunch showed attorneys clearly declaring that their calls were covered under attorney-client privilege, effectively telling anyone listening in that the call was off-limits.

TechCrunch spoke to two attorneys, whose communications with their clients in prison over the past six months were recorded and transcribed by HomeWAV, but asked that we not name them or their clients as doing so might harm their client’s legal defense. Both expressed alarm that their calls had been recorded. One of the attorneys said that they had verbally asserted attorney-client privilege on the call, while the other attorney also considered that their call was protected by attorney-client privilege but declined to comment further until they had spoken to their client.

Another defense attorney, Daniel Repka, told TechCrunch confirmed one of his calls with a client in prison in September was recorded, transcribed and subsequently exposed, but said that the call was not sensitive.

“We did not relay any information that would be considered protected by attorney-client privilege,” said Repka. “Anytime I have a client who calls me from a jail, I’m very conscious and aware of the possibility not only of security breaches, but also the potential ability to access these phone calls by the county attorney’s office,” he said.

Repka described attorney-client privilege as “sacred” for attorneys and their clients. “It’s really the only way that we’re able to ensure that attorneys are able to represent their clients in the most effective and zealous way possible,” he said.

“The best practice for attorneys is always, always, always to go visit your client at the jail in person where you’re in a room, and you have far more privacy than over a telephone line that you know has been designated as a recording device,” he said.

But the challenges brought by the pandemic has made in-person visits difficult, or impossible in some states. The Marshall Project, a non-partisan organization focusing on criminal justice in the U.S., said several states have suspended in-person visitation because of the threat posed by coronavirus, including legal visits.

Even prior to the pandemic, some prisons ended in-person visitation in favor of video calls.

Video visitation technology is now a billion-dollar industry, with companies like Securus making millions each year by charging callers often exorbitant fees to call their incarcerated loved ones.

HomeWAV isn’t the only video visitation service to have faced security issues.

In 2015, an apparent breach at Securus resulted in the leak of some 70 million inmate phone calls by an anonymous hacker and shared with The Intercept. Many of the recordings in the cache also contained calls designated protected by attorney-client privilege, the publication reported.

In August, Diachenko reported a similar security lapse at TelMate, another prison visitation provide, which saw millions of inmate messages exposed because of a passwordless database.

You can send tips securely over Signal and WhatsApp to +1 646-755-8849 or you can send an encrypted email to: zack.whittaker@protonmail.com

from TechCrunch https://ift.tt/36SQ1H4

No comments:

Post a Comment